Over

the last few weeks I have been doing the Arthur Carhart National

Wilderness Training Center courses on wilderness management.

Through the application of computer technology I have been able to

take these courses on-line through ProValens Learning.

(http://provalenslearning.com/) ProValens

is the outcome of collaboration between

several educational organizations and institutions for the benefit of

those of us working with the National Park Service, US Forest

Service, Bureau of Land Management and US Department of Fish and

Wildlife. These are Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands,

Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center (Univ of Montana),

Indiana University, National Center on Accessibility, National Park

Service, Indiana University Department of Recreation, Park, and

Tourism Studies, Indiana Parks and Recreation Association, World

Urban Parks, and World Parks Academy.

(https://provalenslearning.com/our_partners/) It has been a lot of

hard work but well worth the effort.

Over

the last few weeks I have been doing the Arthur Carhart National

Wilderness Training Center courses on wilderness management.

Through the application of computer technology I have been able to

take these courses on-line through ProValens Learning.

(http://provalenslearning.com/) ProValens

is the outcome of collaboration between

several educational organizations and institutions for the benefit of

those of us working with the National Park Service, US Forest

Service, Bureau of Land Management and US Department of Fish and

Wildlife. These are Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands,

Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center (Univ of Montana),

Indiana University, National Center on Accessibility, National Park

Service, Indiana University Department of Recreation, Park, and

Tourism Studies, Indiana Parks and Recreation Association, World

Urban Parks, and World Parks Academy.

(https://provalenslearning.com/our_partners/) It has been a lot of

hard work but well worth the effort.

One

thing which I quickly learned was that decisions pertaining to the

care and management of the wilderness are extremely complicated. As

was pointed out in my most recent course - Natural Resource

Management in Wilderness: Challenges in Natural Resource Restoration

- the process is complicated by ambiguous legislation and agency

policy, insufficient funds and personnel resources, insufficient

scientific information, conflicting public and personal values.

Three of the four of these are obviously self-explanatory.

Insufficient scientific information is a problem because we don't

have enough long-term studies. Part of the reason for that goes back

to the influence of the other three problems - legislation and

policy, funds and conflicting values.

There

are five wilderness characteristics of which one must be aware when

proposing or evaluating a plan of action in the wilderness:

untrammeled, undeveloped, natural, solitude or primitive and

unconfined recreation and other features of value. One could write

books about each of these characteristics but I'm going try to give a

really brief explanation. Untrammeled is an archaic word but

exceptionally appropriate both in the Wilderness Act itself as well

as in making wilderness management decisions. Untrammeled basically

means uncontrolled. It is the "wild" in wilderness.

Undeveloped means that the area is free of any "permanent improvement" or human occupation. Natural is the quality of a

wilderness' indigenous species, patterns and/or ecological processes.

Sorry, but homo sapiens are not indigenous to any wilderness in

North America. Strictly speaking a very strong, scientific argument

is made that the homo sapien is only indigenous to limited areas of

East Africa. That means that anywhere else we are technically an

invasive species. Solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation is

all about people. I find this a bit objectionable but, because of

the homo sapien's erroneous belief that it is the most important

animal on the planet, it is necessary to have this type of statement

in order to get a law such as the Wilderness Act passed. But my bias

is showing. Sorry! "Other features of value" is a

catch-all which includes archaeological sites or sites of historical interest/importance which may exist within the wilderness area.

When

the wilderness manager must make a decision whether or not to take

action which might be contrary to the law - viz. Wilderness Act of

1964 - they must go through a complex process called a Minimum

Requirement Analysis (MRA). My first prerequisite class was on the

Wilderness Act itself. The second prerequisite was on how to write

an MRA. By law, the decision-maker is only permitted to skip the MRA

in the case of an emergency such as a forest fire or search and

rescue. It is no wonder that decisions take so long. To write an MRA

is a long, laborious task. After you give all the details of the

project in your description, you must determine whether the

objectives can be achieved outside of the wilderness boundary,

whether there are any valid existing right, special provisions, other

laws which might have a say, and the impact on the characteristics.

Once you have determined that action is necessary, then you have to

determine minimum activity. You don't go into an area with a

bulldozer when a single man with a shovel can do the job just as

well. Here you deal with things like time restraint and then list the

component parts of the project, develop and compare alternative

before deciding how the project is going to be done.

If

that isn't complex enough, there are natural conflicts when you start

trying to maintain the characteristics of the wilderness. I'm going to

avoid the obvious; viz. natural conflicts between trammeling and

natural versus unconfined recreation; because I don't want my

personal bias to overshadow the real story. So let's take

untrammeled versus natural as an example.

One

wouldn't think that there should be any conflict. Both are for the

good and welfare of the wilderness. But here's a problem. Howard

Zahniser, the Wilderness Act's author, said, “Wilderness areas are

peculiarly those remnants of our land where the play of natural

forces and man’s accommodation of himself to these forces are to be

insisted upon for the continued preservation of the wilderness and

its special values to man. Those who have the custody of these areas

should manage them with this objective always in mind. As nearly as

possible, wilderness areas should be so managed as to be left

unmanaged.” To be kept untrammeled is to be kept wild and so in

relationship to trammeling we must say we manage people, not the

wilderness.

At

the same time the wilderness manager has responsibility to maintain

the natural quality of the wilderness. And so the question is posed

“What are the obligations, duties and responsibilities that

wilderness managers have in regards to protecting species, their

habitats, and natural processes?”

(http://eppley.org/lms/mod/url/view.php?id=3992) This would imply

that to meet this obligation we manage both people and wilderness.

Do

you see the almost unavoidable conflict? If you do something that

you believe is a part of your responsibility to protect a species

then you are necessarily going to have to do something in the

wilderness which is, by definition, trammeling. Let me share a couple

of examples. They do a good job of showing how complicated the entire

decision making process is.

The

first example is the Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). The Ponderosa

pine needs fire because of their pyriscence cones which are

stimulated by fire to release their seeds. There is an ongoing battle

between agencies - most notably National Park Service and US Forest

Service - about whether or not fires should be suppressed. [Here I

need to clarify that we're talking about fighting forest fires. Since

90% of all forest fires are caused by humans then we want to do

everything we can to help them avoid starting fires.] If we suppress fires the needles of the Ponderosa pine fall to the ground and can

become quite deep. When you add to this the accumulation of other

fuels you have a virtual tinder box. When a fire does start it is

going to be much hotter and more intense because of the abundance of

fuel. When this happens the fire is hot enough to burn through the

bark of the Ponderosa and into the cambial layer - the living

material under the bark - and kill the tree. To avoid this scenario

we might not suppress fires. But such an act, while fulfilling our

obligation to keep the wilderness untrammeled, might permit a

human-caused fire to destroy the last grazing area of a major animal

species. If we do something like rake the duff we might be able to

reduce the severity of the fire so that the tree can survive, but

that is obvious manipulation of the wilderness and therefore

contradicts our mandate to keep the wilderness untrammeled. There is

no absolute answer or absolute right. Decision makers can only work

to make the best decision for their particular circumstances.

Here's

an example right out of the course on Challenges in Natural Resource

Restoration.

"Whitebark

pine

grows in the northwestern United States and Canada. It is commonly

the highest-elevation tree in these regions, and almost 98% of its

range is within United States public lands. Their seeds contain

high-fat, high-energy food sources for several animal species.

Whitebark pine also contributes to watershed health and protection in

their ecosystems. They are an important part of the Natural quality

of many wilderness areas. The Wilderness Act and agency policy

require that managers protect and preserve all of the qualities of

wilderness character, including Untrammeled, Natural, Undeveloped,

Outstanding Opportunities for Solitude or Unconfined and Primitive

Recreation, and any of the Unique quality values that may be present.

However, whitebark pine is severely threatened by two human-caused

problems--introduced disease (white pine blister rust inadvertently

introduced from British Columbia in 1910) and fire suppression--which

are complicated by recent upsurges in mountain pine beetle.

Over

70 years of fire suppression has allowed succession of

fire-intolerant species such as subalpine fir and Englemann spruce to

increasingly replace whitebark pine throughout its range. Whitebark

pine mortality from the combination of blister rust and beetle

outbreaks exceeds 50% in some areas. Less than 5% of mature whitebark

pines have a genetic resistance to white pine blister rust. Natural

regeneration of whitebark pine trees from surviving individuals will

increase the spread of rust-resistant trees. Individual trees might

be protected by application of aerial sprays, but it is expensive,

ineffective range-wide, and may not be ecologically sound.

Mechanically removing the blister rust host species or pruning

infected branches is possible, but expensive and ineffective

range-wide. Seedlings from rust-resistant seeds have been propagated

and planted with good success in non-wilderness areas where the

environment has been restored and is conducive to survival.

In

an effort to allow fire to play its natural and historic role, wild

fires are no longer suppressed in some wilderness areas and where

they pose no threat to human life or property. Will restoration of

whitebark pine forests minimize threats from blister rust disease and

encroachment of other species? Will restoration allow stands to,

eventually, be healthy enough to withstand occasional mountain pine

beetle infestations. Should restoration actions be taken? If so,

which ones?" (http://eppley.org/lms/mod/url/view.php?id=3992)

Doing

the exercises in the course work can be quite humbling. You write a

plan that you believe is really good and it gets totally destroyed.

But the benefits of taking these classes has gone far beyond learning

information and skills that I might use in our work with the National

Park Service. They have opened my eyes to the gigantic task which

has been given to our wilderness managers. These are tasks having

tremendous impact upon our land and our world for which those given

the responsibility are not given adequate funding or resources

nevertheless any financial reward for their efforts. They often have

to find their own funding and make their own resources. Their reward

is seeing the fruits of their labor of love. Thankfully, that is of

great value and importance to them. It definitely makes me feel

proud to be one of their resources and I hope that taking these courses will enable me to be of greater service to them as a resource.

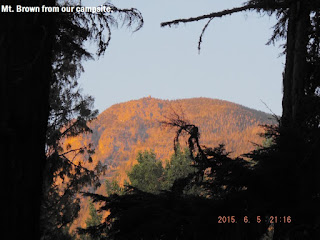

I

am able to take these classes because I work the for the National

Park Service as a volunteer. Pamela and I, like the other NPS

volunteers, have a contract with the NPS so we are treated like

employees. We are also members of the Glacier National Park Volunteer

Associates which is a major resource and partner of Glacier National

Park. If you would like to investigate the possibility of taking

some of these courses, please drop me a note and I'll help as much as

I can.